What’s Latin For Delivering On Digital Customer Expectations?

Why do we put locks on exterior glass doors? Why would a business extend credit to a customer with merely an illegible signature on a purchase ticket? Why do we make promises to customers based on the future performance of vendors?

Yes, there are laws and consequences that address missteps or misbehavior in all of these scenarios. But are those elements really what make us extend and expose ourselves?

Post hoc is Latin for “after the fact.” Laws, regulations, contracts, and other such elements are part of the post hoc process when Humpty Dumpty falls off the wall. They remediate, redress, and reconcile – after the fact. But as important and effective as they may be, they’re not really what drives our behavior.

It’s caused by the antonym of post hoc. Ut prius, Latin for “before the fact,” applies to something more powerful than laws, is a little older than the handshake and the keystone of civilization. That living artifact is trust. And analog humans have been expecting, demonstrating, and receiving it for at least 10,000 years.

But as primordial and powerful as trust is, it has no form of its own and must rely on what I call trust proxies like these:

- Trust is delivered by ethics, which is devotion to the unenforceable (Marrella).

- Trust sounds like integrity, which has no need of rules (Camus).

- Trust behaves like morality, which is commitment to something greater than self (Jesus Christ).

It’s an article of faith to expect trust proxies to work: that a locked glass door will stop an honest person; a customer will justify our trust expectations and pay the bill; and vendors won’t leave us hanging.

Of course, our forebears handed down these expectations from their absolute, 100% analog world. But in the third decade of Earth’s first digital millennium, you and I have a different reality. Today, there’s an increasing disconnect between expecting trust and getting it. And there’s the rub.

As if in Rod Serling’s “Twilight Zone,” we’re the first generation of humans to live and work in parallel universes. Every day we operate with one foot in the diminishing analog world from whence we’ve come and the other in the emerging digital dimension into which we’re being thrust. And as Alice discovered in Wonderland, things here are different.

Having been imprinted on analog legacy institutions – like trust proxies – it’s still our nature to expect analog responses, behaviors, and results, even as we immerse ourselves in the universe where we’re more likely to find:

- Analog resolutions determined by artificial intelligence.

- Physical work replicated by robots.

- Face-to-face interaction digitally delivered to a two-dimensional screen.

As exciting and productive as digital leverage can be, raw binary code is by definition devoid of trust proxies unless and until the 100% analog creators convert it into digital DNA and install it in an algorithm.

No pickpocket standing in front of a judge ever mounted a successful analog defense with, “It was my fingers – they did it.” No teenager testing the forbearance of a weary parent avoids reprimand by claiming: “Not my fault. I was left unsupervised.”

And yet, in conversations with Big Tech representatives responding to inquiries regarding trust-proxy breaches that harm small businesses and encroach on individual property, privacy, and rights, these inhabitants of Siliconland literally say, “The algorithms did it.” Then, incredibly, and without any sense of shame, irony, or trust awareness, “We have no control over that.” This has happened to me, and I see you nodding your head. #GODHELPUS.

It’s as essential as ever that analog humans continue to desire and expect trust proxies as the foundation of relationships and interactions. But with Einstein’s definition of insanity in mind, as we race hell-bent-for-light-speed toward an increasingly digital existence, what does it say about us when we expect to find a trust proxy in a digital tool if such a concept was never installed there?

In her book Weapons of Math Destruction: How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy, recovering quant Cathy O’Neil wrote that digital leverage “…tends to favor efficiency, while fairness is a squishy, hard-to-quantify concept. For all their advantages … computers still struggle mightily with concepts.”

Of course, the concept of fairness is the essential trust proxy that undergirds laws and contracts.

You may sell the same things your grandfather’s customers purchased after ringing the bell over the front door of his store, but your customers are more likely to arrive through a digital door. What effort are you making in your digital dimension to match their analog expectations with trust proxies at every binary touchpoint?

Your transactions are based on the same currency as when you first opened for business, but it’s likely neither you nor your customers touch the money that “changes hands.” When analog humans become digital customers, they still desire that most powerful trust proxy, peace of mind. Quick! What do your peace-of-mind algorithms look like?

In more than twenty years, one of the great experts on trust, Dr. Arky Ciancutti, has taught my radio audience that trust isn’t just the right thing to do, it’s an immutable business best practice that delivers customers you can’t run off and piles of profit. Trust is more powerful than a quad-core microprocessor, faster than a speeding gigabit, and able to leap the tallest algorithms.

Against Siliconland, trust and all its proxies are a small business’s most powerful competitive tools. But you have to install it in your digital offerings and deliver it ut prius. It doesn’t work post hoc.

Write this on a rock … As long as inhabitants of the digital dimension are analog humans, they will require the living artifact of trust – and all of its proxies.

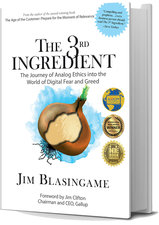

Jim Blasingame is the author of The 3rd Ingredient, the Journey of Analog Ethics into the World of Digital Fear and Greed.